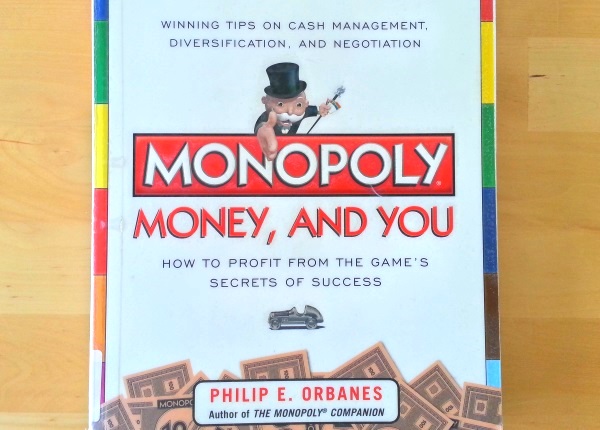

One of the most well-known board games can also be a great way to learn about money and investing - according to this book.

Perhaps one way to teach kids (and maybe ourselves) about finance is to play a board game. In so many ways, the game parallels our own financial life - and we can practice financial decision-making without losing any real money.

Is monopoly like life?

Yes and no. We manage our cash, negotiate, make deals, make choices, go through tough times, make investments, pay tax and reap rewards.

To do well we have to make investments. It's very hard to win just by collecting $200 each time you pass go.

There are rules, and wise moves. The better we know them, the better we do.

However, in real life, you can win without forcing others into bankruptcy.

Principles that work in the game and life

Diversify. You might have hotels on the two most expensive properties on the board, but if no-one lands on them, you still might lose.

Investments have a price and a value. They are not necessarily the same. Understanding value helps you determine whether the price is too high or a bargain.

Finding the ideal amount of cash. Holding on to too much cash means missing out on investment returns. Not holding enough means getting hit hard by expenses and missing out on new investment opportunities.

It's a mix of luck and skill. If you're a winner, other players may think it was luck, but a large amount of the success comes from wise decision-making, maximising your chances, and being in a position to benefit from any luck that comes your way.

The game has phases. In Monopoly, it's buy, build and bankrupt. In life, it's accumulate, grow and withdraw.

Wealthy people are wealthy because their money is working for them - rather than them working for money.

In summary

This is a fascinating book if you've played (or play) Monopoly. There are a lot of tips purely on how to play better at Monopoly - so if you've never played, then that could be a bit tedious. Also the author refers to the properties on the American board, so if you're not familiar with that board, then it loses some meaning.

The intelligent approach to the game, and the connection to real life finances is quite interesting.

It's also got me interested in playing the game, for the first time in a long time.

Related reading

See my other reviews or subscribe to my monthly email for future ones.

Comments

Post a Comment